Amazigh visual arts are very interesting for the scholars and culturologists today because the Berber crafts of weaving and embroidering traditionally are deeply symbolic and centuries-old. Besides, the folk patterns, colors that are commonly used, and the weaving loom itself haven’t changed much since at least the 14th century or even earlier. The Amazigh culture is one of the most preserved in the world, despite the fact that today most of the Berber textiles and jewels are produced for tourists rather than for their own use. And this culture is really amazing.

Amazigh visual arts are very interesting for the scholars and culturologists today because the Berber crafts of weaving and embroidering traditionally are deeply symbolic and centuries-old. Besides, the folk patterns, colors that are commonly used, and the weaving loom itself haven’t changed much since at least the 14th century or even earlier. The Amazigh culture is one of the most preserved in the world, despite the fact that today most of the Berber textiles and jewels are produced for tourists rather than for their own use. And this culture is really amazing.

This material is based on the lecture of Professor Cynthia Becker, scholar of African arts specializing in the arts of the Imazighen (Berbers) in northwestern Africa.

Amazigh weaving loom

Women in Morocco weave on vertically mounted looms to make a variety of textiles. Some for personal use, some to be sold.

The origin of this loom remains unknown but most scholars believe that this type of loom circulated in the Mediterranean during antiquity.

The similarities in the Amazigh weaving from Tunisia to Morocco we tribute to the portability and the versatility of the vertical loom used by women.

The loom is made from wooden beams that can be easily taken apart, placed on your back, and transported around. This particular loom has some metal poles that run vertically. This is done because the artisan makes textile for the export market and so she works all the time. So she wanted to make her loom more solid and wasn’t planning on moving it.

But most of Berber women use portable weaving looms, they move from place to place, and it causes the spread of similar patterns throughout Northern Africa.

Amazigh weaving techniques

The craft of wool working includes washing, combing, spinning wool into thread, dyeing (synthetic dyes have been used in Morocco since the late 19th century; prior to this, women dyed threads with saffron, indigo, henna, turmeric, and other natural materials).

Amazigh women use a flat-weaving technique that includes inserting the weft threads horizontally through the warps that are held apart by a heddle rod and a shed stick.

Except for the flat-woven textiles, Amazigh women are famous for their carpet-weaving as well. But their flat-woven textiles are especially well-known around the world.

Here, you can see that a woman uses a small iron comb with a wooden handle to put the weft threads into place.

Also, in this photo, the female is using synthetic threads instead of wool. She is making sort of a rag rug made from discarded secondhand fabric. And these have become really popular recently. Many people have been collecting these in years. But another reason why local women started to make such rag rugs is because of the changes in climate – it is today difficult for people to keep large herds of sheep for wool, so women started to buy textiles at the market and shred them to make carpets.

Giving birth to textiles

But regardless of the material that is used to make a carpet, there’s a great deal of symbolic meaning that surrounds the loom. Women are said to metaphorically give life to a textile, and when the warp threads are attached to the loom, textile is said to be born and have a soul. Some Amazigh weavers physically straddle the warp threads before the loom is even raised, symbolizing the metaphorical birth of the textile.

The textile then overgoes youth, maturity, and old age as it is woven. And when a woman cuts the textile from the loom, she actually splashes water on it, and she says a prayer, much like someone would pray for a deceased person and wash the body of a dead person.

So, the textile underlies the woman’s reproductive and creative powers. And by equating textiles with human’s passing to the life cycle, it reinforces the centrality of women’s art to Amazigh society.

Embroidery and weaving on female handmade shawls

In the past, women created hand-woven shawls for themselves. The specific styles varied from region to region, but typically, they feature intricate geometric patterns. They would have 2 cords of heavy wool attached to one of the long sides, with a help of which the textile could actually be draped over woman’s shoulders.

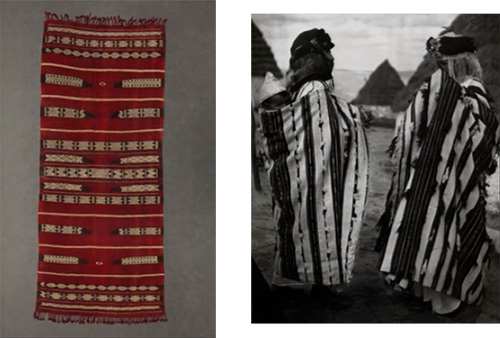

Here are two interesting pictures.

On the left, a woman’s shawl, Central Tunisia, early to mid-20th century. Collection of Yale University Art Gallery.

On the right, a photo of women in Central Morocco, photo by Jean Besancenot, 1934-39.

In the left, the weaver used cotton thread to create geometric patterns. Cotton was often used because it enhanced the textile’s decorative qualities. But women really preferred to work in wool, because wool has “baraka” (blessing). And some of the baraka from the wool transfers to the weavers. It is said that a woman who weaves 40 carpets during her lifetime is guaranteed a place in heaven. Weavers are very much respected within a local community.

Woman’s headshawl, Matmata, Tunisia, mid-20th century. Yale University Art Gallery

This particular woven headshawl from Matmata in Southern Tunisia includes weaving as well as embroidery. So, embroidery is also an art form that links people across Northern Africa. This consists of red and yellow circular tie-dyed patterns at the bottom. And the rest is a solid-woven background dyed with indigo. There’s embroidery at one end that would have been done by a specialist or an Amazigh woman or sometimes a Jewish tailor would do this. Such headpieces were worn for special occasions, such as weddings.

This particular technique is from Matmata. It’s a very remote area in Southern Tunisia. And why is it special? Because the tie-dye technique probably suggests the connection to West Africa. You don’t see so much tie-dye farther north, it’s a rather southern practice. Tie-dye is done is Sierra Leone, all the way to Nigeria. And the existence of this technique on both sides of the Sahara suggests a historical connection between these two regions.

This piece is important because when we look at art on the African continent, usually, we see the influence of North Africa on South Africa, so influences move from north to south. But this is an example of influence from south to north.

The embroidery that we saw on the previous shawl resembles embroidery that’s found elsewhere in the Northern Africa – in Southeastern Morocco.

Rear view of Berber head covering, Southeastern Morocco

This particular type of head covering was started to be made by women in 1970s. Brightly colored yarn became to be available at local markets. Initially, women in Southeastern Morocco wove vogue-colored shawls for themselves and dyed them with indigo. The 1970s is a time when colorful yarn became available, as well as imported fabrics (polyester, cotton). So, women started to buy the fabrics at the market and embroidery them with patterns that you see here.

Regardless of the introduction of new materials into Southern Morocco, the style of embroidery on this sample and the previous one shares a lot of similarities. In both cases, women treated the textile as an empty canvas and they used a running stitch to embroider designs. Both Moroccan and Tunisian folk embroidery featured figurative symbols, such as stylized plants, repeating triangles, and even 5-fingered hands.

The hand is very significant. 5 is an auspicious number because there are 5 obligations of Islam and Muslims pray 5 times a day. This symbol is also said to protect from the evil eye.

Berber fertility and prosperity colors in weaving

Other motifs and colors used to embroider on textiles across North Africa are seen on this sample.

Siwa bridal dress from Egypt. Textile Research Center, Leiden, 1997

Local women wear gowns like this on their wedding days. The opening has a series of 7 different squares around the V-shaped opening. And there’s a series of embroidered patterns that radiate out. 7 is a very important mystical number in Islam. When people go to Mekkah, they circle the Kaaba 7 times. And heaven is said to have 7 gates.

So, the patterns on this gown are definitely the reference to Islam, but there’s also a reference to the Amazigh heritage, the connection across various areas of North Africa. We see the addition of mother-of-pearl buttons here, so the whole thing would shimmer in the light. A lot of scholars say that such a textile shows the influence of a Sun-worshiping cult that used to be popular on this territory a long time ago. It means that this common visual culture has existed for 2,000 years.

Also, there is a reference to female fertility in this pattern. And this is the most important aspect of this particular textile.

The Amazigh women across Northern Africa use the same designs and the same colors in embroidery. They commonly use black, yellow, orange, red, and green when they weave their carpets or when they embroider or when they paint leather bags, like you see here.

Painted leather bag, Southern Morocco, mid-20th century

Rather than to see these colors as an evidence of a Sun-worshiping cult, it is more logical to consider them the colors that mean fertility and prosperity. Women actually compare these colors to the ripening dates on a palm-tree.

Amazigh wedding clothes

The association of these colors with female fertility is also demonstrated by the clothing of Amazigh brides during the wedding ceremonies. They wear red readdresses, amber, yellow and orange colored clothing. The tassels are green. There is a black cloth on the bride’s back. So, all of the “fertility” colors are used.

Berber protective motifs in textiles

Also, women often used red wool to weave protective motifs of textiles, even those created for their fathers, husbands, and sons.

For example, in the Siroua Mountains, men use a hooded cape called “aknif”.

Cape (aknif), Siroua Mountains, Morocco, mid-19th century. Art Institute of Chicago

This one was woven from dark-brown or black wool and decorated with a long elliptical design that’s woven in red. Such patterns are often interpreted as a protective-eye motif.

These capes exist in museum collections all over the world. And they are a very distinct item of male attire. They’re even mentioned by early travelers to Morocco from the 19th century. They’re made from very heavy goat or sheep wool. And this one was actually woven in one piece. Women would start at the hood and then weave the rest of the garment.

At the beginning of the 20th century, such capes were rarely made anymore because of the amount of labor that was required. Men in Morocco don’t wear the aknifs today, but they are still made for the tourist industry.

These motifs resemble greenish-blue geometric designs that Berber women commonly tattooed on their bodies (faces, hands, ankles) when they reached puberty. The tattoos and textile patterns are similar.

Amazigh women in Central Morocco. Photo from: Berber: Tribal Carpets and Weavings from Morocco, 1991

Why did Amazigh females want to tattoo on their bodies the same symbols that they use in weaving?

Close-up of woven textile from Central Morocco. Private collection

The patterns here are typical for Amazigh textiles across Northern Africa. The zigzags are very common, diamond motifs, series of triangles, etc. Most of such symbols are believed to protect from the evil eye. And they are among the most important and widespread symbols for the Amazigh people. Though, female traditional tattoos have almost faded from existence these days, it’s rare to see anyone with them today, only some elderly women who’ve made them when this tradition was still widely practiced.

Some symbols are not tattooed but just painted on the female body with henna. For instance, for the wedding ceremony, women put special patterns on their hands and feet.

Henna is often used to decorate textiles that are worn by the bride. Here is a piece that is put on the bride’s head before the wedding.

Woman’s head and shoulder mantle called “adghar”, Morocco, early to mid-20th century. Yale University Art Gallery

What’s interesting about this is that it would be completely covered. This garment would be dyed with henna, placed on her head, and then her entire head would be covered with a red silk scarf. So you wouldn’t even see this mantle. It is meant to be more protective than decorative.

Amazigh traditional weaving today

Nowadays, wedding ceremonies serve as one of the few occasions when Amazigh women continue to wear textiles and jewelry that are associated with their ancestors.

Amazigh weavers in the Middle Atlas region of Morocco. Photo by Cynthia Becker, 2000

In the last several decades, the rapid urbanization, the increase of Arabic influence, and the climate changes have profoundly impacted the Berber daily lives. However, local women continue to carry Amazigh arts to the future. Although women may make textiles for tourists and not for themselves, they still teach their daughters how to weave. They recreate the motifs that date back to at least the 14th century, if not earlier. These are motifs that are associated with fertility and protection.