The exhibition “Discovering American Indian Art” at the McClung Museum of Natural History and Culture shows us the way of life, customs and traditions, and folk handicrafts of the Native Americans. Elegant beading patterns, masks for the cannibal dances, outstanding headdresses and other accessories that can surprise you in many ways, items that represent a mixture of centuries-old beliefs of American Indians and casual lifestyle of White settlers, and many other pieces that belonged to Native American tribal people.

The exhibition “Discovering American Indian Art” at the McClung Museum of Natural History and Culture shows us the way of life, customs and traditions, and folk handicrafts of the Native Americans. Elegant beading patterns, masks for the cannibal dances, outstanding headdresses and other accessories that can surprise you in many ways, items that represent a mixture of centuries-old beliefs of American Indians and casual lifestyle of White settlers, and many other pieces that belonged to Native American tribal people.

Dr. Jefferson Chapman, director of the McClung Museum:

We're very excited here, in the McClung Museum, to have this exhibition and I think the title “Discovering American Indian Art” says it all. We wish to convey to the museum visitor an understanding and an appreciation of the diversity and the incredible artistic ability of the Native American peoples of North America. This is part of the museum's fundamental mission, which is to develop an awareness and an appreciation of the earth and its people, so this fits very clearly into it. We're also extremely appreciative of the couple who loaned us these pieces from their collection. They have a deep abiding interest in the subject and were very excited when we suggested that they share that with the public.

It's been a huge success – we've had many, many schoolchildren in here, University students and classes as well, so it's an exciting educational experience. We're very appreciative and very fortunate to have two scholars on the Department of Anthropology Faculty who have served as curators of this exhibition, selecting the pieces, writing the labels, and, clearly, conveying all this exhibit has to say.

Dr. Mike Logan and Dr. Gerald Schroedl will be taking you through this exhibition and focusing on some of their favorite pieces and pieces of significance.

Dr. Michael H. Logan, Department of Anthropology of The University of Tennessee, Knoxville:

The exhibit that we curated is drawn from a remarkable private collection amassed over a period of some 30 years by a very adventuresome couple in Tennessee. When invited to curate the exhibit, Gerald Schroedl and I were confronted with a number of problems. First, the title of the exhibit – and we chose “Discovering American Indian Art” – and this reflects the couple's literal journey of discovery as they traveled throughout the United States and Canada, purchasing items from dealers of Native American artists. So, “Discovering American Indian Art” is a reflection of their travels and their educational growth in the material culture of North America's Indian people's.

Native American headdresses, adorned with beading and embroidery

Approximately, 75 objects are open for public viewing and the exhibit. Moreover, Dr. Schroedl and I were uncharged with developing various themes through which the pieces in the exhibit could be best displayed and interpreted by the viewing public. There are 6 primary themes in the exhibit. The first of these, as you can see in this map behind us, reflecting the great cultural diversity of Native American art.

Dr. Gerald F. Schroedl, Department of Anthropology of The University of Tennessee, Knoxville:

Dr. Logan is referring to how anthropologists organize information about American Indians, and largely, this is done in terms of what is called “culture areas”. There are 10 generally recognized culture areas in native North America, and the collection represents all of those culture areas. Some, of course, are better represented than others. Once we had identified out to see the different cultures, then we selected pieces from the collection to reflect other themes.

The 10 culture areas in native North America are:

- Arctic

- Subarctic

- Northeast Woodlands

- Southeast

- Plains

- Great Basin

- Plateau

- Northwest Coast

- California

- Southwest

Dr. Michael H. Logan:

So, these themes, going from artistic diversity, raw materials, contact and trade, beadwork, functional roles, and, lastly, indigitization give in our mind a sense of cohesion to the immense diversity of the material items on display and the exhibit.

Dr. Gerald F. Schroedl:

I might add that most of the items in the exhibit date from the 20th century, but in the collection, there are some very fine pieces that date to the 19th century. The earliest material in the exhibit dates to around the 1820s. There are a few items from the 1860s, 1880s, and then more contemporary materials from the 20th century.

Beading on a vintage Native American purse

When Dr. Logan and I constructed the exhibit, we wanted to have the viewer get a sense of the context of the objects, and it was for this reason then, that we included historical photographs where we could, alongside the exhibits. Many of these photographs were done by Edward Curtis in the early part of the 20th century. He was pretty famous for photographing American teens throughout the western United States and, fortunately, here, at the University, there is a complete collection of his portfolio photographs which we were able to borrow from the museum and to incorporate those alongside the objects. So the person viewing an object can actually see how a native person might have used that object or worn that object, or the context of the use of that object. And I think this adds a great deal to the experience of the viewer.

Weaving pattern of Native American Indians. Storm pattern Navajo rug

Dr. Michael H. Logan:

All too frequently in exhibits, you lack the human dimension – you have material things strung on walls, they set there silent, and we wanted to incorporate these historic photographs to bridge the material items to the peoples who produced and used them. And I think the cases that we have here with photographs do exactly that. A Navajo weaver at her loom and then the storm pattern Navajo rug; the sacred Lakota pipe and then a man, Plains Indian, holding a sacred pipe quite similar to the one on exhibit. So, Dr. Schroedl and I feel quite good about the ability to integrate the human element into the exhibit through use of these photographs.

Artistic diversity

Dr. Michael H. Logan:

One thing is abundantly clear in viewing the items contained in this exhibit, and that is the exceptional diverse range of material items used by native peoples. Simply consider three bags: this Plateau bag, Lakota pipe bag, and the MicMac bag over here. Exceptionally diverse, although they all held a functional role quite similar to that of storage. These were containers, yet the artistic treatment is highly diverse on each of the three of these items.

Dr. Gerald F. Schroedl:

Virtually, all Native American peoples manufactured baskets and, of course, the Cherokee people here, in the Southeast, made some of the finest baskets that we know of. And even today, they continue to make these baskets. So, this is a fairly contemporary of what is called a “double weave basket” where there's actually two walls to the basket, and these are very, very finely made. People today, as I said, continue to make these and they can even be purchased by people who are interested in collecting things like this.

Double weave basket made by Cherokee people

Raw materials

Dr. Gerald F. Schroedl:

The first thing has to do with the raw material from which different artifacts are constructed. This would include things like ivory, and bone, and metal, and stone, and a variety of raw materials.

Dr. Michael H. Logan:

The sacred pipe. This is a Lakota pipe, specimen dating to about 1870. The decorator would dye porcupine quills, ribbons, Mallard duck feathers. And then, the bowl of the pipe is made of red-colored stone occurring in Southern Minnesota. We have the two pieces of the pipe separate – when joined, they become sacred and with the rising smoke, the prayers of the people are carried to the upper sky world.

Indians in the Southeast part of the United States became eminently skilled in the construction of cloth shirts, dresses, and skirts. Much of the material they acquired from items discarded by White's. They would re-cut them and then very carefully sew them together somewhat patchwork-style to make these beautiful and very distinctive forms of dress. This shirt, dating to about 1940, and this is Seminole in origin.

Seminole shirt, 1940. It is made in a patchwork-style

Dr. Gerald F. Schroedl:

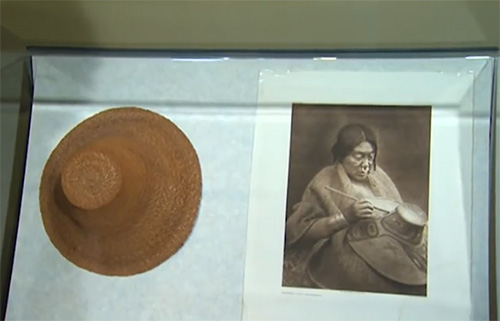

Native Americans on the Northwest Coast of North America manufactured capes, and baskets, and hats, such as this – out of spruce root or cedar bark. And, of course, the Northwest Coast being very rainy, these hats were very useful. In some cases, as shown in the Curtis image, the hats were painted, and the images painted on the hats represent spirits that were associated with the particular social groups amongst the Haida, the Tlingit, the Kwakiutl, and other people of the Northwest Coast.

Cedar bark hats made by Indians from Northwest Coast of North America. The photo shows a process of painting such hats

Contact and Trade

Dr. Gerald F. Schroedl:

Next part of the exhibit has to do with Contact and Trade. As Dr. Logan and myself have studied a great deal, obviously, when Native Americans were in contact with one another, they acquired raw materials and different ideas about the construction and style of different objects from one another. And then, of course, once the European contact occurred, the Native Americans also began to borrow ideas and borrow things from Europeans.

All native peoples constructed elaborate costumes and dress for various ceremonial purposes. In this case, we have a young lady from the Umatilla tribe of the Columbia Plateau region, in the Northwestern part of North America. And she's wearing a wedding veil over the top of her head. Here, we have an example of a wedding veil that's virtually identical to the one shown in the Curtis image. What makes this a particularly interesting object is all the different materials that were gathered – both locally available materials as well as materials that were purchased or traded for to construct this veil. For example, it includes glass trade beads and these white dentalium shells (these are type of shell that is found only in the Northwestern part of North America), and then, we have these cowry shells that had to be traded in, and there are some little teeny-tiny brass bells, and then, these various round objects (one of those is a Chinese coin and the others are brass arcade tokens that were acquired by the native people to help construct this wedding veil).

Wedding veil from the Umatilla tribe of the Columbia Plateau region

Dr. Michael H. Logan:

A great ingenuity of Native American artists, of taking items gathered through sale, or purchase, or trade and then reutilizing them in a manner consistent with their own culture and artistic traditions. The rear part of this wedding veil we have is a number of sewing thimbles that had been perforated and strung for their purposes on this wedding veil.

Beadwork

Dr. Michael H. Logan:

Next of our themes is the Beadwork. Glass beads, perhaps more so than any other trade item, enjoyed the greatest value among the Native Americans. Beads in quantity were shipped from Italy, originally Venice, across the Atlantic to the United States, and then shipped out west and traded in a variety of different venues to Indian people's. The women of these tribal nations became eminently skilled at this craft of applying glass beads to various hides or later, to trade cloth. So, beadworking is something that is seen in virtually all of the culture areas of Native North America.

Beading on the Native American moccasins

Dr. Gerald F. Schroedl:

Here, we have two of what are referred to as “octopus bags”, and the reason they're called “octopus bags” is because, as you can see in the picture, they have these long tabs and it sort of reminds people of the legs of an octopus. Of course, there are actually eight of them because there's two behind. When and where people started calling them octopus bags is not quite known but bags like this were thought to have originally been made out of fur and that the long tabs represent where the legs of the animal were left on the bag. And then, of course, during the contact period when the Native Americans started making these out of cloth, they continued that design but used cloth and beads to actually manufacture the object. What's interesting about these particular kinds of bags is that they apparently were first made in eastern North America and then the style and idea of the bags diffused across most of North America.

Octopus bags made by Tlingit people, Southern Alaska

Dr. Michael H. Logan:

As an artifact type, these bags are extremely interesting. They appear first in historic written accounts of Whites observing Indians with these very distinctive type of bags. In the eastern region of Canada in the 1600s, with the expansion of the fur trade further west and north through Canada, this style of bag diffused from group to group, eventually going into Southern Alaska. These bags here attributed as Tlingit, Southern Alaska.

Beadwork on one of the octopus bags made by Tlingit people

Dr. Gerald F. Schroedl:

As the bags or the idea of these bags diffused across northern North America, each native group added its own distinctive touches so that almost all these bags can be recognized to a specific ethnic group. For example, the reason we know that particularly this bag is Tlingit is because of the very distinctive frog motif and also some of the characteristics of the detail, of the way the beadwork is done which is very distinctive to Tlingit’s. So, even though the bags all look superficially the same, they are fairly easy to recognize as to what part of North America they were originally constructed.

Functional Roles

Dr. Michael H. Logan:

Functional Roles is another of our primary sub-themes in the exhibit. By functional roles, such things as utilitarian rolls, storage bags or baskets, ritual items or ceremonial items, the exquisite pieces of Northwest Coast wooden masks, religious pieces, even toys played a prominent role in socializing children and the activities associated with their daily life as adults.

This is a spectacular specimen created in Eastern Canada. It is a hood for a woman. It would be worn not on a daily basis but for only special occasions – a wedding, for example. The amount of work required to decorate this in beads is really hard for me to adequately explain or convey – it took the consummately skilled beadworker thousands of hours of daily work to complete this spectacular beaded hood.

Beadwork on a female hood from Eastern Canada

These moccasins with the beaded soles, common among the Lakota or the Western Sioux, are known as “honoring moccasins”. The woman who beaded these went to the extra step of beading the sole. Her additional work was a gift of honor to the person who received these as a gift, thus the term “honoring moccasins”. With the extra beadwork, she is honoring the recipient of these moccasins. Many historic pairs that I have seen show signs of wear. We also have photographs of men wearing these types of moccasins with the solid beaded soles.

Beaded moccasin, known as “honoring moccasins”, with a beaded sole

Dr. Gerald F. Schroedl:

This is a particularly interesting Northwest Coast hat that is attributed to the Nootka people. As you can see, it's made out of woven cedar bark and then, woven into the pattern of the hat are these images of whales. These are called “Maquinna hats” because they were first observed by James Cook when he visited the Northwest Coast in the late 18th century and a chief by the name of Maquinna was wearing one. They've been known as Maquinna hats ever since. The image here is an actual 18th-century engraving associated with the Cook expedition that was done by a man named John Weber – he was the artist with a Cook expedition. Here, you can see a Nootka woman wearing a hat in the late 18th century that's virtually identical to the hat here that we have on display that was made in the 1970s by a Nootka woman.

Northwest Coast people are famous for their construction of a variety of masks that they use in ceremonies, and in healing, and a variety of other kinds of activities. And, of course, when Europeans first came to the Northwest Coast, they observed native people making and using these masks in very elaborate ways. But out of the course of contact and particularly in the 19th and early 20th century, the Canadian government was very concerned about the activities that Native people were using these masks in. They banned masks and they banned many of the ceremonies. And it was in the early 20th century that mask makers like Willie Seaweed, and Mungo Martin, and others began to revitalize the mask making tradition. Today, that is shown by this mask and others in the exhibit. Contemporary Native Americans in the Northwest Coast make these masks. And mostly, they're used now for decorative purposes, although many of the ceremonies and the traditions, that the masks were once used in, have also been revitalized.

Ceremonial mask of the Kwakiutl people

This particular mask is a part of the winter ceremonial activities of the Kwakiutl people and this is part of what is sometimes referred to as “cannibal dances”. This particular mask represents a cannibalistic bird – the bird has this very long beak so as literally to come down and hammer a person's head open and eat the person's brains. These ceremonies are largely initiation ceremonies that are conducted during the winter months. Part of the custom in using this mask is that the wearer would literally put this over his head, and you can see the cedar bark that would cover his head and shoulders, and then, he'd be wearing a cape or a costume, probably made out of cloth or cedar bark. The beak of the mask is actually movable so it can move up and down. The individual wearing the mask, as well as many other people wearing similar masks and a variety of other masks on these ceremonies, would literally carry these things around and can conduct very elaborate dances and ceremonies. There are numerous historical accounts of how spectacular these were and how in many ways they were scary and very animated so that the people really enjoyed this as well as participated in these important ceremonies.

Dr. Michael H. Logan:

This is a “possible bag” – that term refers to a bag for every possible thing. It was used to store personal possessions. This bag is particularly interesting. It dates to 1990, and it was made by a medical doctor. The beadworking that we see here faithfully copies an earlier tradition where scenes of battles were beaded onto garments, to pipe bags, to shield covers. We see a man here, a Lakota warrior with the feathered bonnet, mounted on his horse, charging an enemy. And we know the ethnic identity or tribal identity of the slain enemy – he is the Crow: the pompadour hairstyle, the Loop Style necklace, and the lower panel leggings. I should also point out that the horse's tail has been bobbed, and that was a universal symbol on the Plains that the man riding that horse was on the warpath. This bag shows very forcefully that Indian peoples here are very much with us today, they have viable cultures, and their artistic traditions continue strongly.

So called “possible bag”, 1990. It has an interesting beaded pattern depicting a battle scene between two Native American tribes

Indigenization

Dr. Michael H. Logan:

The last theme of the six is Indigenization. This is a process whereby Native peoples would borrow items and ideas from Whites and then incorporate them into their own culture and treat them aesthetically according to their own tribe's traditions.

Small vest for a young Lakota boy, embellished with American flags

This is a spectacular specimen. Of all the pieces on exhibit, this is perhaps my favorite. It's a small vest for a young Lakota boy and, as anyone can see readily, it is embellished with American flags. This is a paradox of great proportion. Simply ask why would oppressed peoples, American Indians, specifically the Lakota or Western Sioux, why would they incorporate the preeminent symbol of their oppressor – the US government and the Army – and incorporate that symbol into their applied ethnic art? Art historians have suggested that the flag represents the ongoing warrior image. I disagree. This was made in 1890, the very last thing the woman who made this for her young child would want to convey to White power holders is that the young boy and his family were hostile to the government. Rather, this symbolized the Indians’ deep desire to live, to coexist peacefully with Whites. Certainly paradoxical – 1890 is the year that the Army slaughtered so many innocent Indians at Wounded Knee.

Beautiful leather gloves decorated with embroidery

We hope you've enjoyed this presentation on the Discovering American Indian Art. This is the type of exhibition that the museum does 3 times a year, all of them designed to meet our mission, to educate the public, and to develop an awareness and a deeper appreciation of the world and its many, many diverse cultures and peoples. The McClung Museum is on the University of Tennessee campus. It's free and open to the public, and we are open 357 days out of the year. We have both permanent and temporary exhibitions and you'll find it to be a very meaningful experience to come by.

(c)