We’ve already published a number of articles about Gentleman Jack series and the stage costumes used in it, but the topic of film fashion is immense and it is much more interesting to analyze the period-accurate garments used in the movies than in portraits or books. So, here you are another material dedicated to the mid-19th-century clothing in Gentleman Jack, a recent and very popular historical drama TV series. Let’s look at the costumes from the POV of a fashion historian.

We’ve already published a number of articles about Gentleman Jack series and the stage costumes used in it, but the topic of film fashion is immense and it is much more interesting to analyze the period-accurate garments used in the movies than in portraits or books. So, here you are another material dedicated to the mid-19th-century clothing in Gentleman Jack, a recent and very popular historical drama TV series. Let’s look at the costumes from the POV of a fashion historian.

Read also:

Stage costumes of Gentleman Jack series, a scandalous 2019 historical drama

Gentleman Jack stage costumes. Extravagant and historically accurate outfits of Anne Lister

Women’s stage costumes in Gentleman Jack: Ann Walker and others

The article is based on a video by Amanda Hallay, fashion historian

In case you haven't seen this movie or aren't that familiar with the story, Gentlemen Jack is based on the diaries of a real-life lady called Anne Lister, who was an English woman living in the 19th century. She was an industrialist, something of an architect and landscape designer, a landowner, and a diarist. A lot of her diaries were written in code because she was also a lesbian.

The costume designer for Gentleman Jack is Tom Pye.

Usually, costume designers tasked with creating female wardrobe for a show set in the 1830s modify it so much that it's unrecognizable. Why do they modify it? Because the 1830s female fashion silhouette was bizarre. And so they modify it so that it reads as sexy and attractive to the modern eye. Tom Pye did not do this. He kept all of it in its bizarre glory. When it comes to female fashion in the 1830s, people fall into two camps – either you love it or you think it's extremely unflattering and bizarre.

The reason that Tom Pye and director Sally Wainwright decided to keep the female costumes in Gentleman Jack true to historical form is because they wanted Anne Lister's character and her mode of dress to really stand out against the other characters to show that she was different, she was a maverick, she did not fit in with the mores or the aesthetic of the women around her of her era.

Let's take a moment to consider this really odd 1830s silhouette and why it happened. There were, basically, no shoulders at all to a garment for a female, and then suddenly these huge gigot sleeves with sleeve plumpers. The waistline wasn't empire but it wasn't at the waist either – it fell somewhere sort of in-between.

So, the silhouette was very dainty, it was very childlike and doll-like. This was the era of acquisition, this was the Industrial Revolution. And the Industrial Revolution impacted fashion more than any other thing impacted fashion in the 19th century.

Although you can't see the feet here, hemlines became a little shorter, adding to this doll-like overall aesthetic. The era of acquisition and, certainly, the era when a woman's place was as a wife or a mother or a daughter – she was sort of the property of her father or husband or brother, and then when she got older, of her son. Anne Lister had a very different idea to a woman's place in 19th-century society.

There was a lot going on with this silhouette at the time. If you add the pelerine, this lace cape with pointy ends that was fastened over a garment, the upper part of the body becomes very, very wide.

This was an era when people got rich quick. This was the era of the burgeoning nouveau riche. People were living large. And so the silhouette got large.

Add to that a lot of bows and lace and a deep-brimmed bonnet, and we have this uber feminized, rather strange, very wide, but dainty silhouette.

You can see why most costume designers modify it today when recreating it on screen. But Tom Pye didn't, and it makes such a wonderful contrast with his wardrobe for Anne Lister, which he based very much on her own diaries in a discussion of clothing.

It was bold of Tom Pye to keep this massive silhouette on screen. It works so perfectly, though.

Throughout the 19th century, adornment equaled wealth. And in the 1830s, with the burgeoning nouveau riche, the more adornment you had, the more successful and wealthy you were. And you were showing your newfound wealth off with bows and ribbons and lace and feathers and artificial ringlets, but not always. And this is where Tom Pye really is a genius because he also costumed to character and to scene.

This is Anne Lister’s sister Marianne from a wealthy family, but here she is at home wearing a wool dress and she has taken her sleeve plumpers out, because for more casual, intimate, at-home moments, even wealthy young women and ladies took their sleeve plumpers out.

Sleeve plumpers were often attached to the underpinnings or a corset and then you would actually stuff them with these little bags that were full of soft downy feathers. And you could either just have your sleeves a little bit flat and more comfortable or puff them up to really show off how wealthy and fashionable you were.

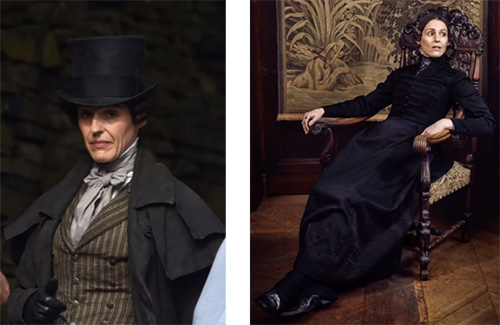

Let's look at Tom Pye’s vision for his costumes for Anne Lister. He based her wardrobe on the real Anne Lister, on the few portraits that exist of her, and from her diaries.

Naturally, a lot of this is based on menswear of the 1830s. She dresses almost exclusively in black or dark tones, as did all men of this era.

He said in an interview that he originally tried putting her in pantaloons but that it didn't seem right, it seemed too far-fetched. This takes place in Halifax in the 1830s – no woman would have worn any kind of trousers or pantaloons or breeches. So he put her in skirts, as the real Anne Lister wore.

There is so much attention to detail in the wardrobe of Anne Lister in the movie – fob watches and velvet trim and neckerchiefs. A lot of the garments were actually drawn from Anne Lister’s diary. For example, she spoke about wearing her spenser, and so he designed her spenser.

Tom Pye did admit in an interview that he cheated with Anne's signature top hat because the real Anne Lister did not wear a top hat. Evidently, she wore a flat black velvet cap, but the top hat is so iconic and eye-catching.

And the costume designer said he didn't feel he was being entirely anachronistic because he looked to images and etchings of the “Ladies of Llangollen”, a famous same-sex couple of the same era, who were famous for wearing top hats.

Let's talk about the hair and makeup and Gentleman Jack. The makeup designer was Lin Davie and the hair designer was Sue Newbould. They did a fantastic job, including the addition of artificial ringlets and curls. Artificial hair was a big thing in the 19th century. Many women wore fake hair in this period – Charles Dickens writes of it.

The only time in the whole series that Anne Lister wears white and conforms to feminine fashion aesthetics of the 1830s is in the final episode.

(c)