The new historical series “Gentleman Jack” shows us extraordinary costumes of the mid-19th century. It is very interesting to review these outfits because the show is based on a real story and costume designers had to make the clothes of these movie character counterparts as close to their prototypes as possible. But what is even more impressive is that the main characters of this series are two lesbians. How do you dress a high-society lesbian from the 1830s? Based on real-life statements, not just designer’s imagination!

The new historical series “Gentleman Jack” shows us extraordinary costumes of the mid-19th century. It is very interesting to review these outfits because the show is based on a real story and costume designers had to make the clothes of these movie character counterparts as close to their prototypes as possible. But what is even more impressive is that the main characters of this series are two lesbians. How do you dress a high-society lesbian from the 1830s? Based on real-life statements, not just designer’s imagination!

Read also: Gentleman Jack stage costumes. Extravagant and historically accurate outfits of Anne Lister

Women’s stage costumes in Gentleman Jack: Ann Walker and others

This material is dedicated to the stage costumes of “Gentleman Jack”, a 2019 historical drama TV series. These costumes are so unique because the movie tells about 19th-century lesbians, and it is a true story based on a bunch of decoded diaries. Intriguing, isn’t it? So, let’s get started.

But first, we’d like to mention that this article is based on the video from a YouTube channel “Costume CO” (you can find the link at the end of the article).

The story is based upon the diaries (from 1832) of real-life landowner and industrialist Anne Lister, portrayed in the show by English actor Suranne Jones.

The costumes were brought to the small screen by costume and set designer Tom Pye. Tom researched the costumes of “Gentleman Jack” through a variety of means – he studied painted portraits of the era and he spent a lot of time gaining access to original clothing kept in museum archives around the country, such as The Bath Museum, Chertsey, Bankfield, Winchester Museum, and the John Bright Collection in London.

Here's an example of this type of silhouette of a woman's costume from the early 1830s. This dress is dated circa 1830 from the John Bright Collection.

This American cotton dress with gigot sleeves from The Met dates between 1832-1835. “Gigot” is a French word for “leg”. This style of sleeve is also called “leg ‘o’ mutton” or “leg of mutton” because of its resemblance to a mutton leg. And according to The Met, sleeves like this were popular from the 1830s through 1836, when they began to diminish to the tightly fitted sleeves of the following period.

This cotton&linen dress is dated between 1830-1835 and it's also from The Met.

Here is a detail of the dress’ fabric. The myth states that the fashions during this time allowed the textiles to stand out because of the vast surface area of the skirt and a relatively minimal amount of access trim.

Inspiration ideas for costumes

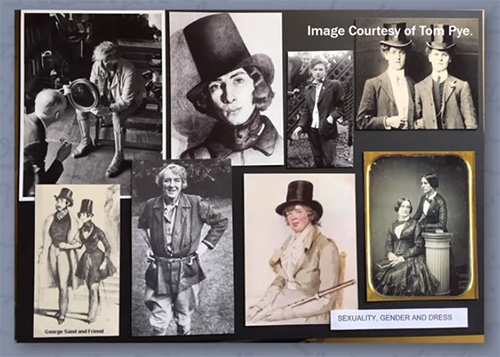

Here's some of Tom Pye's research that includes mood boards or influence boards. These are both dated from February 2017 and are titled “Sexuality, gender and dress”.

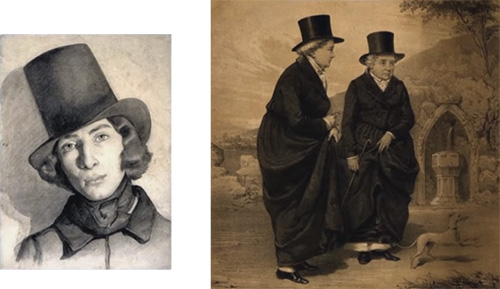

Tom says that the idea for the top hat came from the Ladies of Llangollen and from George Sand. Sand was one of the most notable 19th-century women who chose to wear male attire in public. In the late 18th century, the Ladies of Llangollen escaped unwanted marriages in Ireland before fleeing to Wales with a servant. Both women were said to dress in black riding habits and men's hats. Anne Lister was said to have visited the couple.

Here is another influence board that Tom has titled “Pelisses, redingotes and military influences”. The pelisses or redingotes are long women's outer coats, like the ones pictured on the left.

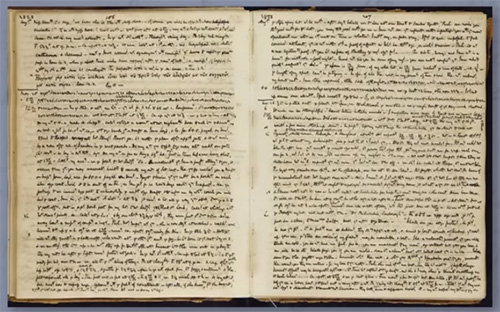

Pictured here, is Anne Lister’s last diary entry from August 11, 1840, just six weeks before her death.

Tom Pye said, “I spent a lot of time with Anne Lister's diaries, too. In them, there are plenty of mentions of her clothing, including her corsets or stays, skirts, her spencer jacket, her greatcoat, gaiters, waistcoats, petticoats, and pelisse. This all gave me a good framework to begin with”.

One of great aspects of the show are the estates and the beautifully designed interiors that compliment the costume so well.

Tom Pye said that he had a great time collaborating with production designer Anne Pritchard, who designed the scenery and oversaw all of the props and furnishings. “We always shared ideas about forthcoming scenes and as this series progressed, I knew which wallpapers and rooms the characters would be playing within, and in knowing so, I very deliberately coordinated the costumes with the interiors”, he adds. “But sometimes this worked totally organically”.

Where did they get fabrics and trimmings?

Tom has great many resources at his disposal and when it comes to sourcing up fabrics, he casts his net very wide and states that finding the right fabrics is half the job.

“Modern-looking fabrics can kill the finished look of a costume”, says Tom Pye, “and there could be nothing you can do to rectify this”.

Tom said, “Trims, buttons, ribbons, and the like are relatively easy. I bought a lot from car boot sales and antique markets. In fact, I never stopped doing that – most weekends I'm out at car boot sales”.

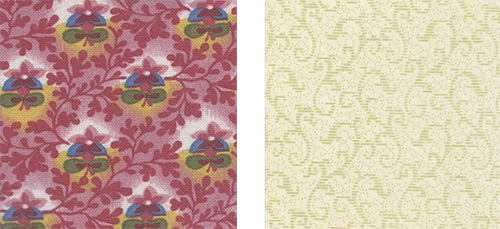

Online sellers Etsy and eBay can be useful as well. They always have a big stock of vintage trims. In the USA, there are several great companies reproducing original 18th- and 19th-century prints, like these 1830s reprinted cotton samples.

Another source to get handmade fabrics and trimmings that imitate authentic pieces are local craftsmen and small manufacturers.

Thousands of costumes for the show

With an assortment of custom-made and rented costumes gathered from a variety of sources, it's impossible to know how many costumes were used in Season 1. It was possibly in the thousands.

They had one scene in the first episode with 200 background artists for just one day. Most days in the street scenes, they had around a hundred and their costumes varied enormously, depending on whether they were agriculture workers, factory workers, or wealthy London society.

So they did need an awful lot of costumes. At one point, they had four trucks full of stock. As the season developed, they literally ran out of costumes.

With this many costumes to rent, build, alter, and fit on actors and background players, you might think that Tom had an enormous team at his disposal, but actually, the costume department was very small. They didn't have tailors or permanent dressmakers on set, everything was built either at Cosprop in London or by freelancers.

Headdresses in “Gentleman Jack”

While the tailoring and costumes are fantastic, one of the standout features of “Gentleman Jack” are the 19th-century hats.

Tom Pye worked with a really fabulous milliner Sean Barrett.

On bigger scenes such as the wedding, Sean put a small team together to help redress all the bonnets, but the main principle hats he made himself.

Undergarments in “Gentleman Jack”

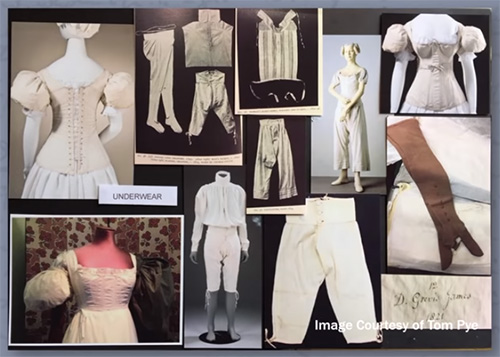

Here's Tom's reference and influence board for the underpinnings that you don't get to see on screen.

These are pads worn under the gigot sleeves to hold them up. The Victoria & Albert Museum in London has a pair of original sleeve pads from 1830. It was really helpful for the costume designer to see how they secured to the corset straps. They're, basically, a feather-filled linen bag that straps around the upper arm to hold the sleeves out.

The sleeves look rather sad without the pads. They are rather ridiculous but helpful when you bump into doorways.

Here's another set of sleeve supports from 1828 from the Met. They state that sleeve supports were frequently down-filled pillows but chintz with ribs of wire or cane was also used to make somewhat airier lantern-light forms. And this set are made from cotton and whale baleen.

Costumes of main and background characters are in relation

When Tom Pye designed the stage costumes of “Gentleman Jack” characters, he began with Anne Lister and Ann Walker (the main heroines) and then worked outwards. He wanted everyone else to be in relation to them.

They had a lot of other characters, well over a hundred characters from all sorts of different social classes. The complicated part was that most of them were based on real people, so Tom needed to do as much research as he could to try to keep an accuracy across the board.

For example, the team went to huge lengths in Episode 2 to get Sir Donald Cameron correct. They ended up having his tartan woven up in Scotland for the costume scene in his wedding so that it correctly reflected the real Donald Cameron and his status as head of his Scottish clan. They even sourced eagle feathers for his cap.

Opposed to Anne Lister's largely black wardrobe and the pastel palette of Ann Walker, the Rawson brothers are dressed up in layers of rich jewel tones. The designer dressed the antagonists with these colors because, as Tom Pye says, “I had an idea that as self-made men in the town, they might be quite ostentatious and want to flaunt their status and wealth”.

The actors both loved this idea and ran with it. The wardrobe team had fun dressing them as peacocks, especially Vincent.

In the next articles regarding “Gentleman Jack” costumes, you’ll find the actual analysis of the main characters’ stage costumes, including Anne Lister, Ann Walker, and others.

Read also: Gentleman Jack stage costumes. Extravagant and historically accurate outfits of Anne Lister

Women’s stage costumes in Gentleman Jack: Ann Walker and others

(c)