The European fashion in the 18th century was inspired by France. It was the French court ladies who invented and introduced new trends, new silhouettes, new styles of ornamentation, etc. So, let’s look at the 18th-century women’s fashion with all its diversity and pomp. What did they wear and why? Which garments were the most popular and managed to stay fashionable the longest? What horrible hobbies did French men and women have that destroyed magnificent articles of clothes from this period? And even how the French aristocratic fashion and the French Revolution are connected? We’re ready to enlighten you.

The European fashion in the 18th century was inspired by France. It was the French court ladies who invented and introduced new trends, new silhouettes, new styles of ornamentation, etc. So, let’s look at the 18th-century women’s fashion with all its diversity and pomp. What did they wear and why? Which garments were the most popular and managed to stay fashionable the longest? What horrible hobbies did French men and women have that destroyed magnificent articles of clothes from this period? And even how the French aristocratic fashion and the French Revolution are connected? We’re ready to enlighten you.

The article is based on a video by Amanda Hallay, fashion historian

There really was an ever-changing silhouette in the 18th century. Just take a look at all of those skirts.

But although the skirt shape changes quite dramatically, the bodice actually remains more or less the same throughout the century, with three-quarter length sleeves and a squared neckline. That really was the staple look.

Robe Volante

Throughout the 18th century, there were key dresses – the dresses that everybody wore. And all of these dresses had names. They appeared at different points in the 18th century but some stuck around for several decades.

The first dress comes from the beginning of the century. And it is called the “Robe Volante”, which actually means sort of “flying dress”. You can see where it gets the “volant” from – the panel of fabric that drapes down the back and down the front. But beneath this fabric, her bodice is still fitted to the waist.

Robe Battante

There also were other versions. For instance, the “Robe Battante”. It is not bodiced around the torso, it actually hangs loose all the way around. The Robe Battante followed the idea of the Robe Volante, except that the bodice was looser. Why? Because the Battante was a maternity dress. This is why it stayed popular throughout the century.

Robe a la Francaise

Another gown that is an instant signifier of the 18th century is the “Robe a la Francaise”. It's also known as a “Sacque” or a “Sack Back”. This dress has a long panel of fabric coming from the shoulders at the back all the way down to the floor in a little train (sometimes, those trains got very long). But the front isn't like the Robe Volante – it’s fitted, with a stomacher.

Regardless of decade, a dress with a panel of fabric at the back is known as a Robe a la Francaise. The Robe a la Francaise is sometimes known as the “Watteau Dress” (after the painter Jean-Antoine Watteau). And that’s because many of the people in Watteau’s paintings are wearing such dresses.

People got that fullness at the hip of the dress with a help of a bum roll, which was known as a “romp” in the 18th century.

Robe a l’Anglaise

Another variation was the “Robe a l’Anglaise”, the English dress. From the front, it looks exactly like the Robe a la Francaise but there's no panel in the back.

Again, regardless of decade, a dress without a back panel of fabric is a Robe a l’Anglaise. It doesn't matter what structure the bottom part of the dress takes.

Also, note the split gown with visible underskirt (petticoat). This would be more or less ubiquitous throughout the 18th century.

Robe a la Polonaise

Let's look at another dress from a little bit later in the century – the “Robe a la Polonaise”. “Polonaise” means “Polish”. So presumably, this was a dress that was very popular in that part of Europe, in the royal courts there. And this is what it looks like.

It has a very different bottom half of the silhouette but the bodice is really identical throughout the century. The top layer of fabric was sort of hooched up to make these three folded puffy sacks: 2 at the side and 1 at the back.

Note the ankles! The Robe a la Polonaise was also distinct for allowing women to show their ankles, which was terribly shocking and naughty and sexy.

Robe a la Creole

The next of our popular 18th-century gowns was the Robe a la Creole. It means the “Creole dress”.

The 18th century was a time of tremendous colonization. France claimed a lot of territory in the Caribbean and in a little state called “Louisiana”, which they named after their King Louie. And then they realized that they didn't really want it and sold it to the newly formed United States.

And this is what French aristocrats who were living in the Caribbean or in Louisiana were wearing or presumed to be wearing by the ladies of France. It was a simple white gown but with quite a lot of ruching, quite a lot of pleats, a sash around the waist, and then, this sort of ruffled bodice, ruffled neckline.

Robe en Chemise

And the last of the dresses, we’re going to look at is the Robe en Chemise, which is really a “shirtdress”. It's very different. Tight long sleeves, a square neckline, and just a simple sash. No embroidery, no pannier, no lace, nothing, you could not get a simpler dress.

The Robe en Chemise came about in the 1780s-90s. This new silhouette would absolutely define fashion in the first two decades of the 1800s.

Why did the silhouette (palette, trim, ornamentation) change so drastically and so suddenly? – What happened in 1789 in France that would continue into the first years of the 1790s, that would change not only France but fashion and the world? Of course, it was the French Revolution.

Pannier

This dress is called the “Fanshawe Dress” because it belonged to Lady Ann Fanshawe, who was very happy to walk around with the widest hips in the world. But why would women want to look this way? Let’s find out.

First of all, let us quash the old “child-bearing hips” myth. Some fashion historians say that but it’s a myth. If that was true, why did old ladies wear panniers? why did 7-year-old girls wear panniers? Panniers had nothing to do with the suggestion that women had childbearing hips. It's ridiculous.

This is what it was all about. Remember, the 18th century was defined by man's supposed “triumph over nature” and his embrace of artifice. Everything that was man-made or altered by man or approved by man was to be revered. Even the natural landscape had been drastically altered by man to form something artificial, an artificial man-made environment. This obsession with changing nature, this idea of improving it constantly to produce something extremely artificial and man-made, extended to everything, including the natural silhouette. The natural human shape had to be sort of massaged into something artificial.

But how? How are these garments constructed? Well, with the panniers. “Pannier” is the French word for basket. They were constructed like a basket, they were made out of either reeds or very thin pieces of wood, a light wood, like balsa wood. Panniers are sort of concertina in design, so when you sat down, the pannier would fold beneath you. Sometimes, the reeds or the wood were covered in linen or the entire thing could be covered with fabric.

Along with her pannier, a woman would wear her corset and over her course, her dress would go.

In the 18th century France, even buildings (constructed in the mid-18th century) had wider doors to accommodate the panniers so that women could enter a room front-on, with a modicum of dignity, instead of shuffling into a room sideways. New buildings were made to have very wide doors, because who knew how long the pannier craze would last. Very rich people – if they were living in a building that pre-existed the pannier trend – they simply had their doorways widened. When you visit Paris, a chateau from the 18th century, you'll notice that it has very wide doorways, and now you'll know why.

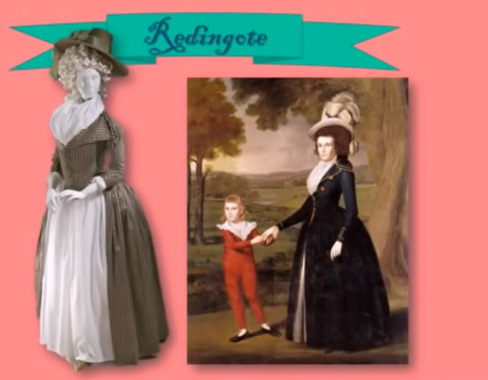

Redingote

Here is a very interesting item. Both men and women wore it – it was tailored slightly differently for each, and it's called a “redingote”. Basically, it's a single (but usually, double-breasted) coat with a very, very wide collar.

Caraco (Caracao)

Another clothing item from the 18th century is the caraco. It was a separate jacket or bodice with a peplum.

Often, it would be made of the same fabric as the skirt – to give it this sort of suit effect.

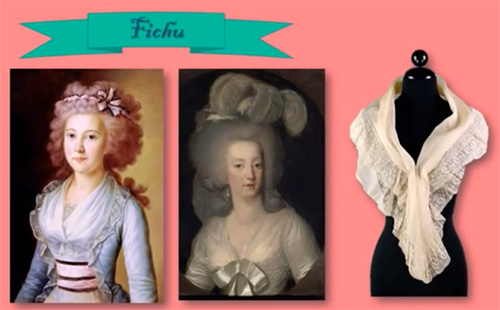

Fichu

In an awful lot of 18th-century female outfits, women are wearing a piece of fabric around their shoulders. And this item has a name, it is called a “fichu”. Sometimes it was plain, sometimes it was lace, sometimes it was sheer, sometimes it wasn't.

And it could also be wrapped entirely around the body and tied at the back.

Other 18th-century fashion trends

Stripes

First of all, stripes were an absolute fixation, an obsession of the 18th century. Stripes were a genuine craze, and they were known as “Peking Stripes”, tying in with the 18th-century interest in something known as “Orientalism” and “Chinoiserie”, which would already peak in the early 19th century.

Gold embroidery

Let's look at gold thread which was actually made of spun gold. It was extremely popular in the 18th century. As was silver thread as well.

When you wear a dress like this, you are saying that you are rich, you are powerful, you are important, you can afford this. Gold thread was not cheap. Neither were the satins and brocade and taffeta – all of the textiles that make up Rococo clothing. And then you add gold to them, you are making an enormous statement.

It would take months and months of care, skill, and pride (often working by candlelight) for people to complete the beautiful embroidery on these pieces.

But if you aren't getting a little bit disgusted with the European aristocracy of the 1700s yet, you will be. The thing is, there was a hobby, little craze amongst the aristocracy of the 18th century called “drizzling”. After wearing one of these gold-embroidered garments only a few times, once everybody had seen them in it, 18th-century aristos would drizzle it.

Basically, they would unpick all of the gold embroidery and pull out the gold threads because they “found it relaxing”. It was relaxing to destroy one of these beautiful garments. The idea was that they would sell the gold thread back to a merchant, but they were rich enough they probably didn't bother. Because after it had been pulled apart, it wasn't worth remotely as much.

Men and women like to drizzle. They would sit around, drinking port, and drizzling – destroying these beautiful dresses and suits.

So these people had no appreciation whatsoever of the workmanship and hours and artistry that went into this beautiful embroidery. And when an institution of any sort is so removed from the workers who service it, something will eventually happen. And that something is the French Revolution.

(c)