Fashion is often so ridiculous that we can’t understand how people can wear that or why do they do it? Here is a story of avant-garde hairdos that were popular in the 18th century. For modern people, these hairstyles may look like a total nightmare but, in that period, it was the norm. Unfortunately, a lot of ladies have suffered from the fashion of the 18th century. Though, today, it is exciting to look back and admire the strength, iron will, and stupidity of the women from Marie Antoinette’s age.

Fashion is often so ridiculous that we can’t understand how people can wear that or why do they do it? Here is a story of avant-garde hairdos that were popular in the 18th century. For modern people, these hairstyles may look like a total nightmare but, in that period, it was the norm. Unfortunately, a lot of ladies have suffered from the fashion of the 18th century. Though, today, it is exciting to look back and admire the strength, iron will, and stupidity of the women from Marie Antoinette’s age.

The royal hairdresser of Marie Antoinette, the Queen of France

What do you know about Marie Antoinette? That she lost her head in the French Revolution? And what do you remember about that head? Most likely, her outrageous poofed and powdered hairdos. In fact, Marie Antoinette has remained a cultural icon for centuries because of the daring style she brought to 18th-century France.

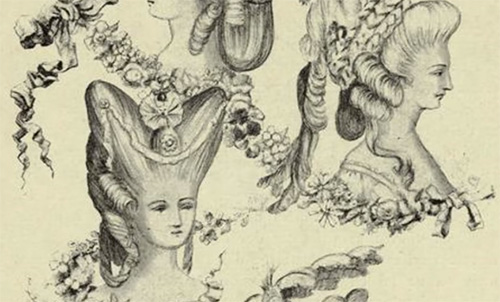

Different hairstyles of Marie Antoinette

And for the better part of the Queen's reign, one man was entrusted with the responsibility of ensuring that her coiffure was at its most ostentatious best. Who was this Minister of fashion who wielded such tremendous influence over the Queen?

Léonard Autié. From humble beginnings as a country barber in the south of France to the inventor of the pouf and the premier hairdresser to the Queen because, as everyone knows, there's no one closer to a woman than her hairdresser. By unearthing a variety of sources from the 18th and 19th centuries, including memoirs, court documents, and archived periodicals, author Will Bashor tells Léonard's mostly unknown story, chronicling his background, the role he played in the life of his most famous client, and the chaotic history-making world in which he rose to prominence.

High hairstyle of Marie Antoinette

Besides his proximity to the Queen, Léonard had a fascinating life, filled with seduction. After all, he was the only man in a female-dominated court. Intrigue, espionage, treason, exile, and possibly execution.

Léonard Autié’s story of life

Léonard was born in the medieval town of Pamiers in 1751. The son of Alexis Autié and Catherine Fournier, both domestic servants. At an early age, Léonard knew he would never find his fortune in the sciences or in government but he was confident that he could take advantage of his two talents: charisma and artistic genius. Greedy for gold and fame, he wrote in his memoirs: “I may very well decide the destiny of my whole life with just a single stroke of my comb”.

Portrait of Léonard Autié

Léonard would have been trained in the art of hairdressing in the mid-1760s in Montpellier and Bordeaux, where he first practiced his craft. But his creative genius was lost on matronly ladies of these provincial cities. To find his fame and fortune, the young man needed to take Paris by storm.

Having made the long journey from Bordeaux, Léonard arrived in Paris on summer’s evening in 1769, after an arduous day of traveling. He was tired, he wrote in his journal, but one couldn't tell. His only luggage was a big bundle of vanity which would not allow him to admit that he had just covered some 120 miles in two weeks on foot.

Léonard noticed that Parisian men dressed according to their rank, wearing small wigs to which they applied powder. Men of higher society wore waistcoats with breeches that reached down to their calves, stockings were then held up with garters, buckled just below the knee. Men of lower ranks normally dressed in the clothes discarded by the wealthier classes, only the cleanliness of the clothes spoke the difference.

Parisian fashion in the 18th century

A young man's poverty follows him wherever he goes, according to a French proverb. But Léonard's rise in the European capital of manners and fashion would hinge on his ability to conform to a certain aesthetic or at least preserve the illusion of it. Unable to afford powder, Léonard styled his hair and whitened it with a billowing gust of flour. With his fine gray waistcoat, brushed until it shined, and the folds of his tie, artistically arranged, he pulled his tightly drawn stockings up to show the calves of his legs. Now, he could surely be taken for a gentleman. If he wasn't quite there yet, he was destined to become one soon enough. After all, Paris awaited him.

What Léonard didn't know however was that hairdressing was highly regulated by the Parisian guild. So, how could Léonard bypass the master hairdressers of the capital city? To answer this, we begin with the theory behind the art of coiffure. According to the manuals of the time, cutting hair was the science of giving natural hair its form by removing irregularities in length and cropping in stages, all the while enhancing the face – the true art of the hairdresser. Therefore, to practice hairdressing, the coiffure would cut the hair according to the client's features and then finished by curling and powdering.

Cutting the hair in the 18th century

The professional, always male coiffeur, would start by combing the entire head of hair to remove any tangles. Then, using his wood, tortoiseshell, or gold comb, he would begin at the top of the head and comb one portion or row at a time, combing straight down or to the side, depending on whether the hair was to be cut straight or angled. When the comb was near the end of the hair, the hair underneath the comb was cut with half-closed scissors. Cutting the hair to the desired length was continued with the rest of the hair, but the top rows of hair were required to be shorter than the lower rows.

Painting depicting the combing of hair

Hairdressing tools were purchased from roaming haberdashers in the 18th century. Clients included wig-makers as well as hairdressers. When styling a wig, one would follow the same rules that govern natural hair – care had to be taken not to cut the wig too short so that it would completely cover all the natural hair below.

Curling the hair in the 18th century

After the hair was properly cut, one wrapped the hair in curling papers, heated the packets with curling irons, and finished with powder. This process required special instruments and materials, used in a precise manner. First, small pieces of paper were cut into triangles, preferably using gray paper or blotting paper, because they tear easily. Gathering a small portion of the hair with the comb and holding it with the first two fingers of one hand around the middle, the coiffeur would roll the hair in a curl and immediately envelop it with the curling paper. This was the “loop curl”.

Curling instruments of 18th-century coiffeurs: curling papers and curling irons

Another type of curl was the “crepe” which was preferable for short hair on top of the head. The crepe was created by taking the strand of hair and twisting it in the curling paper to avoid the hole found in the middle of the loop curl.

Once the whole head was covered with rolling papers, it was time to use the curling irons. The coiffeur used two kinds: one was two-clip with two flat jaws of equal thickness and the other resembled scissors. The irons were heated in the fire. The desired temperature was achieved when the iron did not scorch a curling paper or by testing heat near the cheek. When ready, the curling papers were heated by the iron for a few moments. Another iron would be heated while curling since the irons did not hold their heat too long. With a full head of curling papers, it was necessary to heat several irons.

Various curling irons from the 18th century

Once the curling papers were cooled, they were removed, and the locks of curled hair then combed together. The coiffeur would gracefully arrange the curls around the forehead and temples. If needed, the curling iron, resembling scissors, could reinforce any disobedient curls.

Powdering the hair in the 18th century

The only task left was to powder the hair. The best powder was made of wheat flour and was kept in an iron cup or sheepskin pouch. The best puffs were made with long bristles from the top of the heads of geese. To powder, the coiffeur coated his hands with pomade and lightly waxed the curls. Then, he lightly dipped his puff in the powder. This small quantity was sufficient for dusting the hair and highlighting the cuts in curls. For fear that the clients would get powder on their face and in their eyes, the coiffeur took the precaution of protecting them with a mask.

Process of powdering the hair. The face and eyes of the client are protected by a mask

Hairstyles of the period

Generally petite and arranged close to the head, the “tête de mouton” or “sheep’s head” style was particularly popular at the time and was characterized by soft curls with little or no height. This style can be seen in many of Madame Pompadour’s portraits. The tête de mouton received its name during the reign of Louis XIV. One day, when the King was hunting with one of his ladies of the court, her hair became disheveled during the chase, so he pulled it back and secured it with her garter. Securing the bed of the king that night as well. This traditional style, featuring defined twists of curls that were arranged in rows across the front and top of the head, was popular throughout Europe and commonly included a pom-pom or an ornament, such as small ribbons, pearls, jewels, flowers, or decorative pins styled together. This was named a pom-pom after Louis XV’s mistress – Madame de Pompadour.

Hairdos of French ladies before Léonard Autié

These delicate and demure styles, that frame the face, were the fashion of the time. That is until Léonard arrived. Léonard got a start when vaudeville actress Julie Niébert asked him to style her as a fairy for a pantomime one evening. Lenore's creation was an outlandish diversion, but the means he used and to which he perhaps one day would owe his fame and fortune, were rather simple. He fastened stars to a circle of extremely fine wire, and to this, he attached two pieces of the same wire that he fixed in the hair. The golden stars seemed to arch themselves as a crown on his fairy's head without any visible attachment. “From two steps away”, he wrote, “my illusion was complete”.

Léonard could not believe Julie's delight when she saw the contraption that he had just erected on her head. This petite dancer had received very little praise for her work on the stage up to this time. According to the reviews, she had been somewhat awkward in her gestures and showed little grace in her motion. That very night, however, things changed for the fairy. She became an overnight success and things changed for Léonard, too. Carriages filled with aristocratic ladies lined up in front of the theater to catch a glimpse of his creation. Soon, he was styling the hair of women of the nobility, including the King’s new mistress, Madame du Barry. And by 1772, he had become the hairstylist of the young dauphin Marie Antoinette. Léonard, often taken for nobility, would enter Marie Antoinette's private salon at Versailles soon after her entourage of ladies in waiting dressed her.

It was through the Queen that Léonard achieved his success and fame. But it could also be said that Léonard was indirectly responsible for the very first attacks upon the iconic Queen, found in inflammatory pamphlets circulating this early 1775. The attacks were prompted by Léonard's incredible and increasingly fantastical hairstyles, concoctions that would reach such a height that it was necessary for ladies to kneel on the carriage floor or hold the towering hair pieces outside the coach windows en route to gala balls in the Opera.

Noble ladies of the court of Versailles felt obliged to imitate the Queen's new and daring hairstyles, despite the danger of becoming burning infernos when they brushed against the candles at the palace chandeliers. The young ladies of Paris were also enthralled with the newfangled trends, drastically increasing their coiffure expenses and incurring large debts. Mothers and husbands grumbled, family fights ensued, and many relationships were irreparably damaged. In all, the general consensus of the French people was well publicized: the Queen was bankrupting all the women of France, financially and morally.

Enormous hairdo of a French lady. The caricature

The escalation can be tracked to one evening. Léonard Autié unexpectedly received then Princess Marie Antoinette's request for her signature elaborate coiffure for the Opera. It would be a risky endeavor because he was a bit tipsy. While he slowly separated the princess's hair, attempting to conjure something magical, he no doubt was battling the thumping arteries of his temples. Fortunately, panic gave way to inspiration and, within an hour, his flock of curls was able to hold three white ostrich plumes, set on the left side of her head and fastened in the middle of a rosette he had braided with her hair. A bow of pink ribbon, in the centre of which was a large ruby, held the elaborate creation together.

Marie Antoinette examined it in silence. For a moment, the princess appeared somewhat disappointed but this frown lasted only an instant when, like a flash, her face lit up with delight: “Oh, Léonard, it must be over a yard high”. Léonard agreed that the arrangement was daring but he ventured that there would be 200 hairstyles higher than hers in Paris by the following evening.

Her subjects long to catch a glimpse of the elaborate hairstyles he created and, as he predicted, they soon spared no expense to imitate them. The fervor spread to all of Europe.

The competition

And then, Marie Antoinette's milliner, the celebrated Mademoiselle Bertin, invented a hairdo called the “ques-à-co” or “what is it, coiffeur?”. It was composed of three feathers that ladies wore on the back of the head, creating a design resembling a question mark. And it became the next sensation.

Léonard was very fond of Mademoiselle Bertin, often commenting that their fortunes trudged along hand-in-hand like two good sisters. But Léonard was jealous. In fact, Mademoiselle Bertin's laurels and praise were beginning to prevent Léonard from sleeping at night. He needed just one more of those grand ideas, one that would overthrow all existing Vogue's, not only to win back the favor of the dauphin and assuage his bitterness at Mademoiselle Rose but to keep his name on the tongues of Paris.

Intricate hairdo of the 18th century

After many sleepless nights, Léonard finally came up with a new sensation – Le Pouf Sentimental. It was the spirit of rivalry with Mademoiselle Rose that brought these headdresses to such monstrous heights, both literally and figuratively. The pouf was first worn by Madame the Duchess of Chartres in the month of April 1774. The Duchess's pouf was composed of 14 yards of gauze and numerous plumes waving at the top of the tower. Léonard employed 2 waxen figures as ornaments, representing the little Duke of Égalité in his nurse’s arms. Beside them, he placed a parrot pecking at a plate of cherries and reclining at the nurse's feet. He put the waxen figure of a little African boy of whom the Duchess was very fond. The new pouf was quite unprecedented – never had anyone dared to create such a hodgepodge. Even Léonard was a bit frightened to show the absurd conception at first but, like most of his creations, it caught on swiftly.

Various poufs used by the French court ladies

Soon afterward, one could find the strangest things in the poufs of Paris. Frivolous women covered their heads with butterflies, sentimental women nestled swarms of Cupids in their hair, and the wives of officers wore squadrons perched on their heads. Melancholic women went so far as to put crematory urns in their headdresses. He was also not uncommon to mix feathers with flowers which were kept fresh in tiny bottles of water hidden in the pouf.

A pouf used by the French women

And the hairstyles continued to rise in height. In February 1776, the Queen, going to a ball given by the Duchess of Orleans, had plumes so high they had to be removed from her coiffure to get into her carriage. She had to leave them behind when she returned to Versailles.

The next popular pouf the “Harrison” or the “Hedgehog” was Léonard's concoction of unpowdered hair, curled to the tips and rising in tears, leaving several strands of curls falling on the neck. The hair on the forehead was held up in a high, very large clump with hairpins. The bouffant style was supported by a ribbon that encircled the entire pouf.

Huge poufs popular in the 18th century

Léonard continued to invent new styles, each more extravagant than the next. Some were so high that it appeared that a woman's head was in the middle of her body. Another incredible creation consisted of a ship sailing on a sea of thick wavy hair. It was invented after the naval battle in which the frigate La Belle Poule was victorious. The ship itself with its masts, rigging, and guns was imitated in the miniature on the pouf. This elaborate creation, a celebration of sorts, was an overnight success.

Hairstyle that displays a ship sailing on a sea of thick wavy hair

It should be noted, however, that many such cloths were supported with wired scaffolding and were very heavy. Also, seldom washed and making sleep difficult, these powdered concoctions were commonly breeding grounds for all types of vermin.

The end of an era

By the time Queen Marie Antoinette had given France its first heir to the throne, she was threatened by the increasing loss of her hair. At the first indication of this catastrophe, Léonard began to tremble. Along with the hair of Marie Antoinette, Léonard would lose his power, that supremacy enabling him to open up the hearts of the ladies of Paris and the court, as well as their purses. So, what to do? Léonard persuaded the Queen that his new coiffure “à l'enfant” would meet the same enthusiasm as her previous coiffures. The Queen's beautiful hair fell under Léonard’s scissors and, within two weeks, all the ladies of the court had their hair cut short à l'enfant, creating yet a new era in hairdressing.

Variations of a coiffure à l'enfant

Marie Antoinette with an à l'enfant hairstyle

Marie Antoinette’s hair was the last to go

On August 2nd, 1793, Marie Antoinette was arrested and imprisoned.

Léonard Autié, her celebrated and loyal hairdresser, was in exile in Germany when the executioner arrived at Marie Antoinette's prison cell, scissors in hand. On that chilly October morning in 1793, he tied her hands behind her back and, roughly grasping her hair, cut off the iconic locks that Léonard had made so legendary. Minutes later, the executioner would exhibit the severed Queen's head to the crazed crowds at the foot of the scaffold. Nothing but the continuous roar of “Viva la Nation!” could be heard as he held it up victoriously by her hair.

And so ended the life of Marie Antoinette but not her legacy and influence on the world of fashion. Marie Antoinette, with the help of Monsour Léonard and Mademoiselle Rose, revamped fashion in Paris and in the grand capitals of Europe. Her stunning glamorous costumes and odd avant-garde pouf hairstyle made her the fashion pioneer of the 18th century. The fashion icon in trendsetter of her time also used the yard high boots to tower above her weak incompetent husband Louis XVI.

(c)

Yes, but we gave an active link to your video. This topic is interesting for our readers, and we not only write new articles but also gather useful info. If you don't want your material to be published here, we can delete it. Or we could, for example, mention your name at the beginning.