Vietnamese folk dress ao dai is being used for at least 2,000 years. Of course, it wasn’t changeless – it varied from century to century, from one ruler to the other, from one fashion trend to another. The modern variation of this attire is a mix of Asian and Western culture. Let’s take a look at some important changes in ao dai design. Also, we’ll talk a little about its history. Nowadays, the ao dai is considered one of the most beautiful and feminine women’s folk costumes around the world. Was it always like that?

Vietnamese folk dress ao dai is being used for at least 2,000 years. Of course, it wasn’t changeless – it varied from century to century, from one ruler to the other, from one fashion trend to another. The modern variation of this attire is a mix of Asian and Western culture. Let’s take a look at some important changes in ao dai design. Also, we’ll talk a little about its history. Nowadays, the ao dai is considered one of the most beautiful and feminine women’s folk costumes around the world. Was it always like that?

Most people in the world recognize the Ao Dai as a national symbol of Vietnam. But not everyone knows that to be such an iconic symbol at the moment, the ao dai has been through a significant evolution from where it began. Let's dig into the story of why the ao dai is the perfect fusion of eastern and western culture.

When did ao dai appear?

To be honest, no one’s sure when the Vietnamese ao dai first sprouted its roots, but there is some historical context for us to make our own conclusions.

Theory #1

2000 B.C. – 200 A.D. Dong Son culture

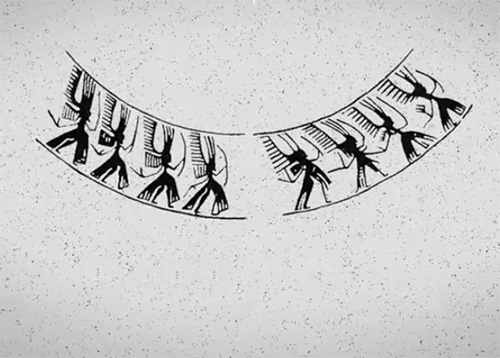

Some experts say that the first sign of ao dai was found on antique bronze drums from the Dong Son culture, before Han Chinese influence. There can be seen people in two-flap tunics depicted on these drums.

Theory #2

38-42 A.D. Trung Sisters

Other experts believe it appeared around 40 A.D., introduced by the Trung Sisters. These two heroines led a revolution against the Chinese Han dynasty and marked Vietnam initial independent state.

So, when was the exact time that ao dai was first introduced? Evidence shows it wasn't until 1744 that ao dai began to make a lasting impression on society.

Ao dai in the 18th and 19th centuries

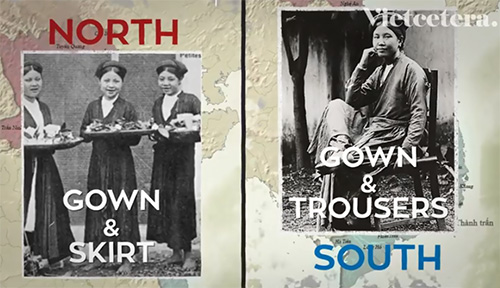

Vietnam was actually divided into two regions at that time. The northern Lords of Hanoi forced their subjects to wear garments called “ao giao linh” – reminiscent of the Chinese robe worn by the Han people, including a front-buttoned gown and skirt. The southern regions of Vietnam demanded that members wear trousers covered by a long silk gown, inspired by Champa-style attire.

Later on, southern people shortened the gown to wear with trousers called “ao ba ba”, while the northern people started the first major evolutionary phase of the ao dai we know today, shifting in order to differentiate between two distinct social classes.

The garb most widely worn by upper-class women during the 1800s was the “ao ngu than”, a 5-panel gown consisting of four outer panels: two in the front sewn into one piece and two in the back, adding collar detail along with a hidden baby flap (an alternatives to a bra, which was not yet invented at that time).

That was also the first time the dress had two slits on each hip, which later becomes the standout feature of ao dai that remains today.

On the other hand, the working-class wore a new, more tidy functional design called “ao tu than” or 4-panel gown. In short, ao tu than is another version of ao ngu than, with the two back panels sewn into one piece. The front panels were not connected but could be tied together. As was typical for lower-class clothing at the time, the 4-panel gown is often in dark colors.

Ao ngu than (on the left) and ao tu than (on the right)

Overall, the two dresses initially had much looser silhouettes and were also much shorter than the ao dai we see now since people were not yet equipped with modern sewing tools.

Ao dai in the 20h century

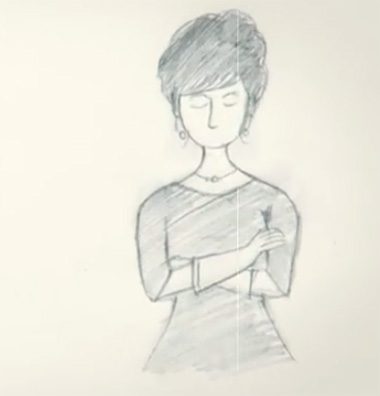

Moving into the early 20th century, the ao dai’s silhouette is fairly loose, with an open collar which allowed the women to show off any necklaces they might wear.

In the next period, 1930-1950s, French colonization had brought up Western influence into Vietnam. Hanoian artist Cat Tuong a.k.a. Lemur varied ao dai into many different silhouettes, taking inspiration from Western fashion.

He tightened up the ao dai more to better fit the form of the Vietnamese women's bodies. He raised the shoulders, extended the dress to reach floor-length, changed to a brighter color scheme, and added Western details like puffy sleeves, heart-shaped collar, and a bow.

In short, he made it sensual, flattering, and appealing to the eye. The design gained popularity over the next 4 years but still, some claim that the design was too sexy and not appropriate to Vietnamese culture.

Soon after that, “ao dai Lemur” was adjusted by painter Le Pho to be more traditional. He cut off the puffy sleeves and replaced them with the details from ao ngu than and ao tu than. From that point on until the 1950s, his version of ao dai – with 2 flaps, tight to the body, and closed at the neck – remained popular, as it was accepted by the more conservative ideology at the time.

However, around the late 1950s, the United States had replaced France as the occupying force. In 1958, Tran Le Xuan, the wife of the president's chief adviser made a controversial fashion statement by wearing a V-neck collar dress with short sleeves and gloves.

Although some praised her for her elegant take on the costume, many others were offended and felt this action was done in poor taste. The distaste for the modern version was so strong that the government banned the dress, as it appeared to serve as an acceptance of capitalist ideals. But was the ban effective? Not really.

In fact, it was in the 60s that ao dai gain the highest level of popularity. Especially in southern Vietnam, since Saigon designer Dung Dakao revolutionized the dress again, with the addition of raglan sleeves. The front panel of ao dai was connected with the back panel by buttons, lined from collar to armpit and continuing down to the side of the hip. With this innovation, the dress showed fewer wrinkles, laying flat on the female body, while still feeling comfortable in movement.

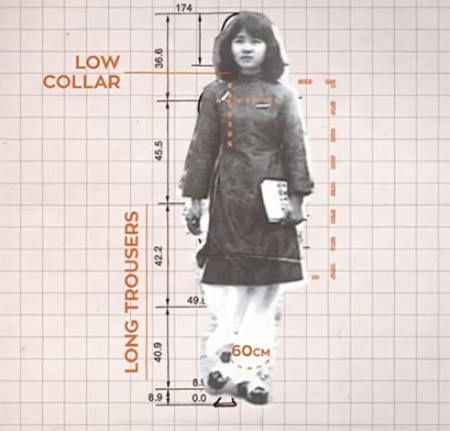

The 70s and early 80s witnessed the country's reform period Doi Moi, along with the wave of hippie culture, embracing the philosophy “Live fast, die young”. Ao dai was modernized with a mini-version: lighter materials, vivid colors, patterns of plants, flowers, and geometric shapes. The bodice is so narrow and short to the knee, with wide body, low collar, and long trousers with wide bell-bottoms up to 60 centimeters. This trend was popular until the mid-90s.

Ao dai in the 21st century

In the 21st century, although being worn less on a daily basis, ao dai still remains as the national symbol of grace, beauty, cultural pride, and creativity. Designer Si Hoang illustrates Vietnamese paintings as patterns on his ao dai, while Minh Hanh is famous for using Hill tribe fabric. Recently, Thuy Nguyen reinvented ao dai with her unique silhouettes and her exclusive use of Vietnamese silk brocade.

As a whole, the Vietnamese ao dai is a dress that everyone, including men, can customize to fit their own taste and figure. From high fashion to traditionalists and everything in between. There's no doubt why this dress is such a treasured element of Vietnamese culture.

(c)

You are right, it's Minh Hanh. Thanks!