In Guatemala, females still wear their folk clothing and thus, make it themselves. Many of them are descendants from Maya people, so they practice the traditional Maya backstrap weaving. The most intricate and beautiful among Guatemalan national garments is a female blouse called “huipil”. We’re offering you a story about how two skilled Guatemalan artisans – Manuela Canil Ren from Chichicastenango and Esperanza Pérez from San Antonio Aguas Calientes – worked on huipiles typical for their regions.

In Guatemala, females still wear their folk clothing and thus, make it themselves. Many of them are descendants from Maya people, so they practice the traditional Maya backstrap weaving. The most intricate and beautiful among Guatemalan national garments is a female blouse called “huipil”. We’re offering you a story about how two skilled Guatemalan artisans – Manuela Canil Ren from Chichicastenango and Esperanza Pérez from San Antonio Aguas Calientes – worked on huipiles typical for their regions.

Guatemala borders the south of Mexico and is a country roughly the size of Ohio. Of the more than 12 million people who live here, just under half identify themselves as indigenous Maya. People who in a myriad of modern ways carry on the cultural traditions of their ancestors. People with a culture as colorful and varied as the weavings they create.

The traditional blouse woven and worn by Mayan women in Guatemala is called a “huipil”. The colors and styles of huipiles vary greatly. Many are identified with a specific community. There have always been changes in adaptations to accommodate new tastes, designs, and materials.

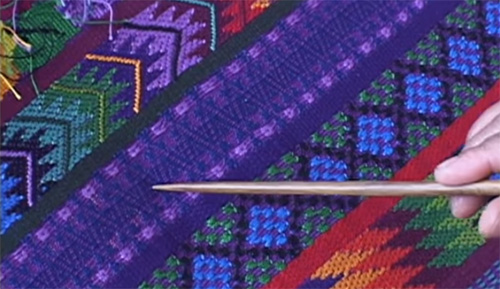

Traditional patterns of Maya weaving

We're in Highland Guatemala to record the making of a huipil from start to finish within 90 days (the length of our visa). Will our craftswomen make it in time?

Chichicastenango

We met a weaver in Chichicastenango who agreed to work with us to record the process of making a huipil on a backstrap loom. Manuela Canil Ren is an accomplished weaver who also works as a vendor in the local market. She lives with her extended family in a labyrinth of linked rooms and living areas near the center of town.

At one of the town shops Manuela chooses the colors and threads, she will use to make our huipil. Speaking in Spanish and K'iche' (Manuela's native language) she and the clerk review the pattern we have chosen from her collection.

Manuela is using a warping board to arrange and measure the threads

The next morning Manuela begins by using a warping board to arrange and measure the warp or vertical threads for the loom. The pegs can be used for different panel lengths. When Manuela is done, she will transfer the warp to sticks which form the backstrap loom.

Manuela is in her early 30s, newly married, and pregnant. Although her husband is rarely present during our visits, Manuela’s family is a constant support. As Manuela finishes the warp, her sister Blanca and father Don Tomas set the hook from which the loom will hang.

With the warp now safely on the sticks, she and Blanca untangle the threads.

In Manuela’s immediate family, we discovered that she is the only one of four girls to continue the weaving tradition:

– Don’t any of your sisters weave?

– No, only I weave.

– Why?

– They don’t like it. They say it takes too much patience.

Manuela concentrates on building the string heddles and adding them to the heddle rod. During weaving, the heddle rod lifts alternate warp threads to produce space through which the weft or horizontal thread is inserted.

As the sun hits high noon, she begins to prepare her loom to be able to finish all four edges of the panel. Rather than cut the weaving from the loom and hem the ends. A four-selvaged panel saves thread but requires skill and tenacity beyond the average weaver. Manuela inserts a rod and attaches cord through the warp loops and secures it. Then she lashes the attached cord to the new end rod. When finished, she pulls out the placeholder rod and attaches the leather backstrap. Her body's pressure on the backstrap controls the tension on the loom.

Manuela begins the weaving

Using a plain black weft thread on a stick shuttle, she begins to weave what will become the finished edge or selvage on one end of the panel.

When we returned from lunch, Manuela has woven four inches of plain weave to stabilize the end of the loom.

Now, Blanca helps her push up the beater, sticks, and heddles in preparation for turning the loom. Since the cotton warps tend to stick together, the process must be done carefully to avoid breakage. Once the loom is turned, Manuela repeats the process of straightening and grouping the warps, she also lashes on an end rod to allow for another finished edge.

By late afternoon, while her nephews play on the lower level, she works to finish the band of plain weave, needed before she can start the colorful and complex brocade designs used in Chichicastenango.

Though her sisters do not weave, they are there to assist Manuela at every step. Her family support will prove to be increasingly important for Manuela in completing this huipil.

Antigua

As a backup, we need a second weaver. For this, we approached Aida Pérez in a colonial capital of Antigua. Aida owns a small museum which traces the history of Maya weaving and indigenous clothing.

Aida seems reluctant to participate but, with her cousin Delaney, goes along to buy the thread. A few days later, when we returned to the museum to film, confusion sets in. The woman at the museum who starts the project is not Aida but her mother Esperanza Pérez. Aida was unfamiliar with the more complex local designs and uncomfortable traveling alone into Antigua each day to be filmed. Esperanza, however, is composed and self-assured.

Like Manuela, Esperanza starts by measuring the thread on a warping board. Then, she counts the warps into groups and bundles them.

Esperanza is counting and bundling the threads

For some, it is hard to believe that these wooden sticks and rods come together to help create a huipil, but as Esperanza sets them up with the warp threads, the loom becomes apparent.

Wooden sticks and rods used to weave huipiles

“This is the most important part of weaving. Without the heddles, the loom doesn’t work. You can’t continue without the heddles”, says Esperanza.

Esperanza begins building the heddles. When the heddles are all on the heddle rod, she passes the end rod through the warps, secures it, and lashes it to the attached chord.

“When I’m weaving, I really like my work”, adds the artisan.

Esperanza is arranging the backstrap loom

She, too, plans to weave a panel with 4 woven edges or selvages. The cord used to secure the warp to the end rod, has come up short, so Esperanza attaches thread to lengthen it. With the economic challenges these women face, improvisation is important. Their substitutions and adjustments display their flexibility and ingenuity.

With the end rod securely in place, Esperanza begins to weave.

Chichicastenango

Chichicastenango transforms itself on market day, becoming an almost overwhelming blend of sights, sounds, and smells that leave your body buzzing. 19 days after our last visit, we find Manuela making slow progress on our huipil. When she sees our concern, she admits she's been finishing another commission but assures us that the huipil will be finished on time.

Weaving pattern typical for Chichicastenango

She explained some of the brocaded designs. Some people use the Spanish word “bordado” to mean both brocade and embroidery. “Brocade” refers to the decorative elements inserted into the weft on the loom, while “embroidery” means designs added to a finished cloth. Weavers in Chichicastenango use their fingers to produce the many brocaded designs typical of their area.

San Antonio Aguas Calientes

“I clothed Aida in native dress from when she was very little. But now, because of our economic situation and how their education costs so much, and because I am a single parent, I sold off their native dress. My husband left. He abandoned us three years ago. I have to work very hard to sustain my children”, Esperanza Pérez tells us. “I started weaving at the age of 7, from age 7 forward. I’m 43 now. That means I’ve been weaving for 35 years”.

Unique to San Antonio Aguas Calientes is a double-face brocading they call “marcador”. Marcador weaving is done with a pick as it is too difficult to do without one.

For many Maya women in Guatemala, especially of Esperanza’s generation, weaving may provide the only viable means of support.

Chichicastenango

Manuela tells us that though she started weaving when she was 8, it wasn't until she was 14 that she learned brocading from her mother. It is the complex brocading that produces the many colorful designs of Chichicastenango huipils. As her pregnancy wears on, her fatigue is more evident and her work slows. We silently lament that the huipil will not be finished before we have to leave.

Antigua

Back at the museum in Antigua, Esperanza continues her work, sometimes drawing attention from groups of tourists. The unique style of San Antonio Aguas Calientes huipiles is very time-consuming and difficult to master. With its intricate technique and numerous complex designs, it requires the focus and fortitude of the weaver.

What do you think about when you weave, we asked her. My mind is only on this, she tells us, if you allow your mind to stray, the lines of your weaving may end up doing the same.

Esperanza works 9 to 11 hours a day to complete the huipil. The work is physically taxing but her weaving is essential to support her family of seven children.

When the streets of Antigua are carpeted with colorful designs for Holy Week processions, Manuela visits for a day to show us how she finishes the center panel of her huipil. Now past the difficult stage of her pregnancy, she has made immense progress.

Using a thin stick and an umbrella spoke, she works the weft through the increasingly narrow opening. The completion of a four-selvaged panel is an exact and painstaking process. When she has closed the gap as much as possible, Manuela can remove the string heddles.

As she works through the finishing process, Manuela surprises us with a recent development in her family: her sister Alicia started to learn Mayan weaving. This is truly surprising since it is a rare instance of a grown Maya woman in Guatemala wanting to turn her attention to learning the art of weaving. Like a language, weaving skills are normally begun as a small child and develop throughout life. Now, as education becomes more accessible and the global culture more visible in Highland Guatemala, fewer Mayan girls are taking up the loom.

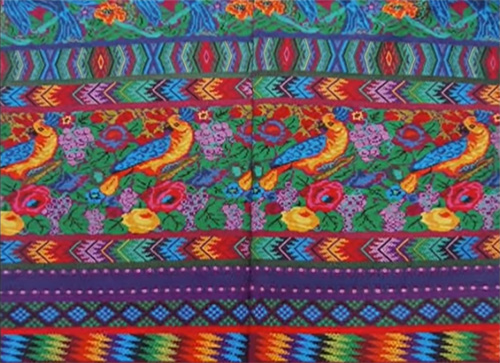

Weaving pattern typical for San Antonio Aguas Calientes

Two days later, we catch up with Esperanza at the museum where she is completing the first of two panels for our other huipil. Along with a sturdy comb, Esperanza uses an umbrella spoke that was once her grandmother's weaving tool. The work is intricate and the process time-consuming.

She can now start to remove the heddles. And in a place where nothing can afford to be wasted, she doesn't. As Esperanza removes the heddles, she wraps the thread around a cardboard cylinder to save and reuse what she can.

The umbrella spoken pick allows her to insert the last few rows. Many hours each day have been spent on this piece. And the two-paneled huipil is coming together beautifully.

Chichicastenango

With just a week before our last scheduled trip to Chichicastenango, we stopped unannounced at Manuela’s and were delighted by what we found: both side panels have been finished. Manuela points out that the hanging threads on the reverse side of the panels will remain uncut. She refers to the 11 colors, making up the huipil, as the rainbow.

Ready woven panel of a huipil from Chichicastenango

When we return for our last visit a week later, the neck has been cut out and finished by a professional embroiderer. Manuela finishes the embroidery that joins the three panels together. Her sister Alicia, toting a new baby on her back, is there to help. The stunning huipil is complete with the traditional Chichicastenango Sun motif neck design at the center of a cross.

Huipil from Chichicastenango made by Manuela

San Antonio Aguas Calientes

With just a few days left before our departure, we arrived at Esperanza’s home for the finishing of the last panel. With the last thread put through, it just takes a few clips. And finished.

Later at the museum with her daughter Aida, Esperanza uses a whipstitch to sew the panels together, forming the huipil.

Ready woven panel of a huipil from San Antonio Aguas Calientes

The finished huipiles are testaments to the skill, perseverance, and tenacity of these weavers. As Western culture and ideals make their way into the lives of the younger generation, this amazing centuries-old art form becomes in danger of being lost.

“The most important thing is to preserve these designs because, with time, these designs could be lost. Because now, many girls study, they don’t weave these designs, and I don’t want the designs to be lost. It’s by generations. The grandmother taught my mother. My mother taught me, and now, I will be teaching my daughters”, comments Esperanza.

Beautiful pattern of a huipil from San Antonio Aguas Calientes

These women struggle daily. But their energy, creativity, and sense of beauty find an outlet in their weaving. They do this in an effort to sustain themselves, their families, and their culture. The creation of huipiles is a tangible art form. It represents both the continuity and change of Maya culture, community, and identity.

(c)

LL for beautiful huilapi?