Indigenous African Yoruba people wear a beautiful garment that was being developed both in their motherland – Africa – and outside the country (in the US and the Caribbean) for decades. This clothing piece has a different name for male and female variation. And for many Africans, it became the symbol of the Black identity and millennial tradition. But how does it look like? And what’s so special about it? Let’s find out a little bit more about the dashiki and buba – such unusual names can’t hide something boring and prosaic!

Indigenous African Yoruba people wear a beautiful garment that was being developed both in their motherland – Africa – and outside the country (in the US and the Caribbean) for decades. This clothing piece has a different name for male and female variation. And for many Africans, it became the symbol of the Black identity and millennial tradition. But how does it look like? And what’s so special about it? Let’s find out a little bit more about the dashiki and buba – such unusual names can’t hide something boring and prosaic!

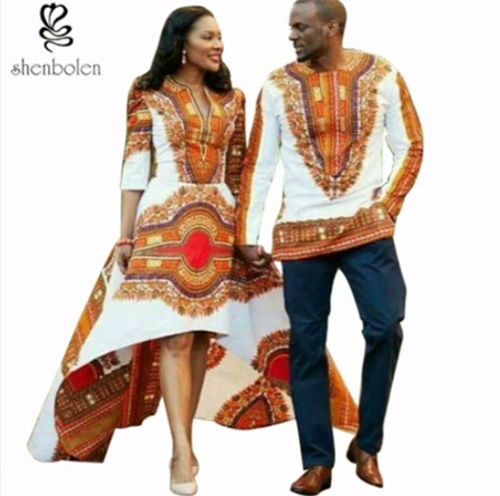

The term “dashiki” is a Yoruba word referencing to the garment worn by men. The garment that is worn by women is called a “buba”. The men's garment is longer, while the women's garment is shorter. And it's sort of a shirt – tight garment that's worn on the upper part of the body.

African man and woman in clothing that is patterned with traditional motifs

Actually, the word “dashiki” comes from the Yoruba word “danshiki”, used to refer to the loose-fitting pullover which originated in West Africa as a functional work tunic for men, comfortable enough to wear in the heat. The Yoruba loaned the word “danshiki” from the Hausa term “dan ciki”, which means “underneath”. The dan ciki garment was commonly worn by males under large robes. Similar garments were found in sacred Dogon burial caves in Southern Mali, which date back to the 12th and 13th centuries.

Colorful dress decorated with traditional buba patterns

Cultural appropriation of this garment can be seen across the African landscape and the Diaspora in a variety of patterns and fabrics, with the Angelina print reaching its heyday in the 1960s and having a resurgence in the late first decade of the 21st century. In fact, various African prints have been used to accentuate several fashion styles and modeling runways. The customary styles, found most prominently in Nigeria and Ghana, have become forerunners, as their acceptance as traditional African garments are most popular.

Why the uniqueness of the pattern doesn’t matter?

It was once noted by one indigenous African that the garment and patterns themselves mean nothing compared to the individual who's wearing them. That is, at certain festivals, one may notice that everyone is wearing the same or similar print garments. The individuals wearing these garments are empowered by their own essence and do not squabble about how another may be wearing the same print. The uniformity may have Westerners shying away from looking alike or wearing something that is the same as another. Buying for their own uniqueness, they often miss that it is the wearer and not the garment that is unique.

African boys wearing dashiki

Once you align yourself with the style, it is also important to know the country from which it is originated. Africans among themselves are quite aware of the distinctions between cultures and styles. They can identify one another based on what they are wearing. However, within the confounds of cultural appropriation and a bit of naivete, a mixing of cultural styles of dress will be seen, particularly in popular modern fashions.

The emblem of Black pride rather than simple stylishness

The roots of the garment are not lost on anyone – it is an unmistakably African item. Its symbolic significance, however, was molded thousands of miles outside of the continent’s borders. It was those of African descent, whose ancestors were hauled to North America in chains, who carried this torch.

Pretty pattern on a modern dashiki

The Civil Rights and Black Panther Movements of the 1960s and early 70s gave the dashiki its political potency. African Americans adopted the article as a means of rejecting Western cultural norms. This is when the dashiki moved beyond style and functionality to become an emblem of Black pride, as illustrative of the beauty of blackness as an afro or raised fist. Its meaning developed in the same vein as the “Africa as Promised Land” rhetoric that fueled movements like Pan-Africanism and Rastafarianism. Perhaps ironically, these Afrocentric philosophies – birthed outside of continental Africa – helped shape some of the fiercest notions about African identity and the politics of blackness.

Little girl’s pink buba

The dashiki’s political vigor weakened towards the end of the 60s when it became popular among white counterculture groups, whose adoption of the garment – based primarily on its aesthetic appeal – undermined its status as a sign of Black identity.

The dashiki lost most of its fervor in the tail-end of the 20th century when its use in the United States was largely limited to ceremonies or festivities, or as pop culture stereotype.

How to distinguish authentic African garments from Asian fakes

At the end of the 1960s and beginning of the 1970s, retailers began to import dashikis made in India, Bangladesh, and Thailand in large numbers. These versions often featured the East African-associated kanga print, commonly worn as wrappers by women in Kenya and Tanzania.

And here is the thing about the products from India, Bangladesh, and Thailand. They were synthetic, whereas the original African fabrics are 100% cotton. They are dyed to the point where it is difficult to determine what side is the right side and what side is the wrong side. There's a lot of material that appears to be African print but if you can see the right side from the wrong side or if you can tell the difference between the two sides, you are not dealing with traditional African print fabrics.

Ghanaian dashiki or Ghanaian smock

And African print fabrics have weight to them – those fabrics that are thicker or heavier are of higher quality, which means when you wash them (and you want to definitely wash them in cold water), but when you wash them, they don't fade and the fabric maintains its buoyancy for many, many years. Whereas those products that were imported from India, Bangladesh, and Thailand, and various other places that were mimicking the African print, they do not endure.

Other African garments similar to dashiki and buba

Also, the larger and more flowing garments worn by men in Nigeria is called “agbada” or, if worn by a woman, is called the “grand buba”.

And the “ntoma”, or large wrapped garment, is worn by both men and women in Ghana, West Africa.

Male ntoma on a man from Ghana

The shorter version of the dashiki in Ghana has been referred to as a “batakari” but Ghanaians will also call the man's top a “dashiki”.

Additionally, the wrap cloth worn by women from the waist down is called a “lappa” by many Ghanaians. It is called “lappa” in the Yoruba language of Nigeria, West Africa.

Modern and very stylish dashiki

(c)